Erik Wengelin was a Norwegian artist, communist, and Nazi concentration camp survivor. Those that knew him described him as a wandering soul and friend to people and animals. His drawings from Sachenhausen provide first hand insight into what prisoners went through in order to survive.

Erik Knut Viktor Wengelin was born on 1 August 1907 in Copenhagen, Denmark. He lived most of his life in Norway and at a fairly young age he joined the communist youth movement and the party and was actively involved in all kinds of activities.

The earliest mention of Erik Wengelin in the Norwegian National Library is in 1924. On 24 May 1924, Wengelin wrote an article in Norges Kommunistblad (Norways Communist Newspaper) with the title “Iron workers, hold on“. In this article we get some insight into his political beliefs.

Ironworkers, hold on.

“You who have fought against hunger and deprivation and suffering through an entire winter. You, who are the hardest of all, have felt capitalism’s bony hand lay clammy and paralyzing over your bum. You who have seen the ghost of hunger creep in on you, you who have seen years of grief and tears poured out on your wife, and your children have become pale and hollow-eyed.

Are you now going to go begging back to work? Will you humbly crawl to the cross? Comrade! It must never happen after all this.

Let your head be as proudly and as defiantly held high now and always. Do not accept the skunks’ brutal wage cuts, but go back to the factories victorious. Persevere, and you, son of iron, will restore the working class’ faith in itself. The world is now in a crisis situation like never before. The capitalists of all countries stand together to crush the spirit of rebellion which is stirring today among the proletariat.

The reaction of the world war has caused capitalist society to shake to its foundations. The workers’ state of Russia has been established, Germany is facing a social revolution, and even here in Norway the exploiters have had their fill, stronger than ever, with the powers that the workers and solidarity possess.

These forces will one day lead the working class to victory, but do not let go of the stranglehold you have gained on the villa owners and business owners with their help.

There must be more powerful means than a strike to stifle them, but hold the roof so long that they gasp for air, they must give in, and then they will feel it for a long time and think twice because they again come up with such reckless and reckless claim.

The iron strike is one of the symptoms of the new coming time.

It is the iron sign of freedom against a stormy sky where the black clouds of reaction chase away in wild chaotic flight.

May your signs not fade and go, but instead flare up and disperse the storm clouds so that the sun of revolution could shine on a newly created earth. Comrade! The choice is yours! What do you want to be, the victor or the slave?

Choose the victory and you can keep your head held high and your back straight!

Long live the iron strike and solidarity!

Live the revolution”.

On 12 March 1938, German troops entered Austria, and one day later, Austria was incorporated into Germany. This union, known as the Anschluss, received the enthusiastic support of most of the Austrian population and was retroactively approved via a plebiscite in April 1938. The Nazis justified the invasion by claiming that Austria had descended into chaos. They circulated fake reports of rioting in Vienna and street fights caused by Communists. German newspapers printed a phony telegram supposedly from the new Austrian chancellor saying that German troops were necessary to restore order.

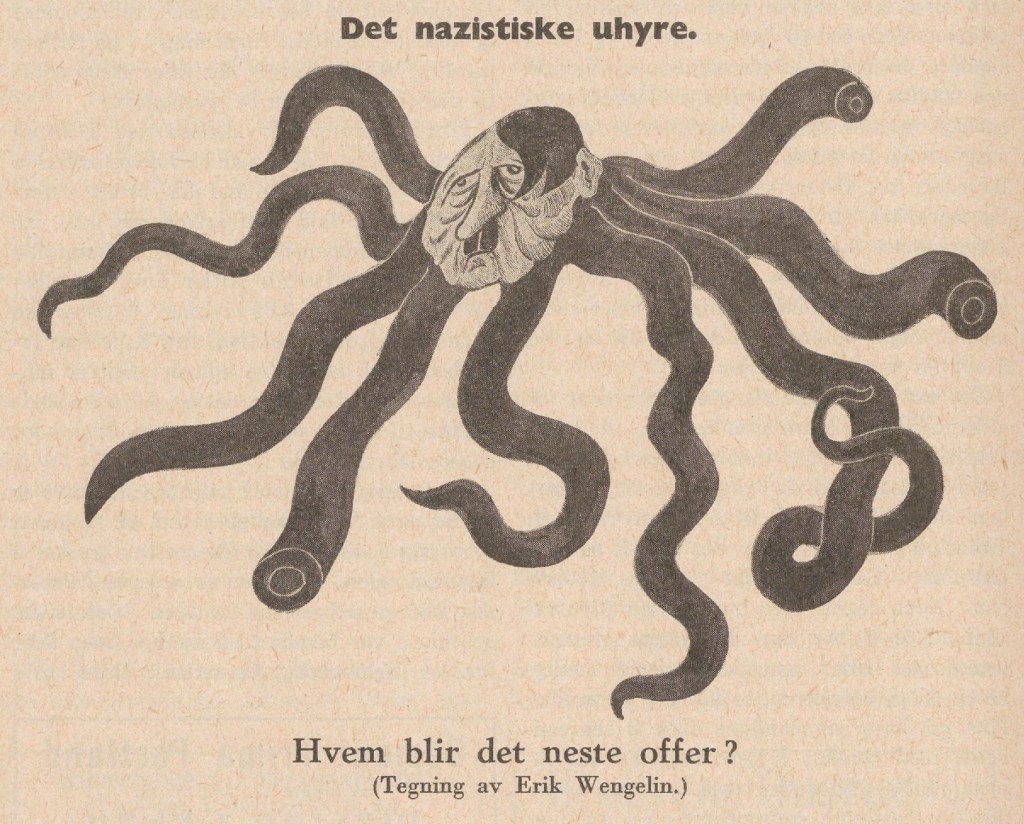

In Bygningsarbeideren (Norwegian construction industry workers’ union). 1938 Vol. 16 No. 5, Wengelin drew the following depiction of Hitler with the caption: “The Nazi monster. Who will be the next victim?“. The drawing appeared at the end of an article about this event with the title “Did Austria fall into Hitler’s hands?”.

Two years later, Norway was occupied by Germany. Erik Wengelin was arrested on 23 August 1942. Three days later he was transferred to Grini detention camp (prisoner number: 4343).

Grini prison camp was a Nazi concentration camp in Bærum, Norway, which operated between 1941 and May 1945. It was originally built as a women’s prison, near an old croft named Ilen (also written Ihlen), on land bought from the Løvenskiold family by the Norwegian state. The construction of a women’s prison started in 1938, but despite being more or less finished in 1940, it did not come into use for its original purpose. Nazi Germany’s invasion of Norway on 9 April 1940, during World War II, instead precipitated the use of the site for detention by the Nazi regime. At first, the Nazis used the prison to detain Norwegian officers captured during the Norwegian Campaign fighting. This use was discontinued in June 1940, when Norway capitulated. The prison was then used to house Wehrmacht soldiers until a concentration camp was established on 14 June 1941. The first detainees were sent from Ånebyleiren, the use of which was at the same time discontinued. Shortly afterwards, the ranks of prisoners were increased by Soviet troops captured during Operation Barbarossa. The camp was run by Schutzstaffel (SS) and Gestapo personnel, who renamed the camp Polizeihäftlingslager Grini. The name corresponds to a nearby farm and surrounding residential district located a short distance southeast of the camp, but historically the area at Ilen had no connection to Grini farm.

At first inmates were detained on the premises of the original prison, but in 1942 an extra barracks had to be built to enlarge capacity. In August 1942, the Veidal Prison Camp was created as a subunit of the camp. Grini was used primarily for Norwegian political prisoners, but the detention of more regular criminals followed. Many were held at Grini before being shipped to camps in Germany; 3402 people in total passed through the camp en route to camps in Germany itself. Similarly, many teachers who took part in the civil disobedience of 1942 were held at Grini for one day before being taken to Kirkenes via Jørstadmoen. A small number of foreign citizens were also held there. Altogether, 19247 prisoners passed through Grini, and at most (in February 1945) there were 6208. Among these were the survivors of Operation Checkmate, a 1943 British commando raid, including their leader, John Godwin, RN. They were subsequently sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp where they were executed in February 1945.

The total number killed at Grini is unknown, though the Gestapo and police often used the area for purposes of torture and at least eight people were executed there. British airborne troops sent by glider to sabotage the Norsk Hydro heavy-water plant during Operation Freshman crashed in Norway due to foul weather. The five uninjured survivors were taken prisoner and held at Grini concentration camp until 18 January 1943, when they were taken to nearby woods, blindfolded and shot in the back of the head by the Gestapo. This was a war crime, in breach of the Geneva Convention. Executions normally took place at Akershus Fortress or Trandumskogen.

Camps in other parts of Norway, including Fannrem, Kvænangen and Bardufoss, were organized as part of the Grini system. German forces also maintained a military camp at Huseby, not far from Grini.

Other than guards, the German occupiers devoted few personnel to the camp. Since many politicians, academics and cultural personalities were detained at Grini, a certain level of internal organization was established. Prisoners worked in manufacturing, agriculture and other manual labor. Much of this manual labor took place outside the camp. Some detainees maintained their pre-war specialties, such as literary historian Francis Bull who secretly held several lectures, and managed to publish three books with material written during his three-year stay at Grini.

The diet at Grini was poor. After the war, it caused a certain stir in the populace when it was perceived that Nazi prisoners of the liberated Norway were treated better than prisoners of the Nazi regime; among other things the diet in Norwegian prisons was much better. On the other hand, Grini was more hospitable to resistance prisoners than the similar camps in Germany.

On 9 December 1943, Erik Wengelin was transferred to Sachsenhausen concentration camp (prisoner number: 73877). Sachsenhausen was a German Nazi concentration camp in Oranienburg, Germany, used from 1936 until April 1945, shortly before the defeat of Nazi Germany in May later that year. It mainly held political prisoners throughout World War II. Prominent prisoners included Joseph Stalin’s oldest son, Yakov Dzhugashvili; assassin Herschel Grynszpan; Paul Reynaud, the penultimate Prime Minister of France; Francisco Largo Caballero, Prime Minister of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War; the wife and children of the Crown Prince of Bavaria; Ukrainian nationalist leader Stepan Bandera; and several enemy soldiers and political dissidents. Sachsenhausen was a labor camp, outfitted with several subcamps, a gas chamber, and a medical experimentation area. Prisoners were treated inhumanely, fed inadequately, and killed openly.

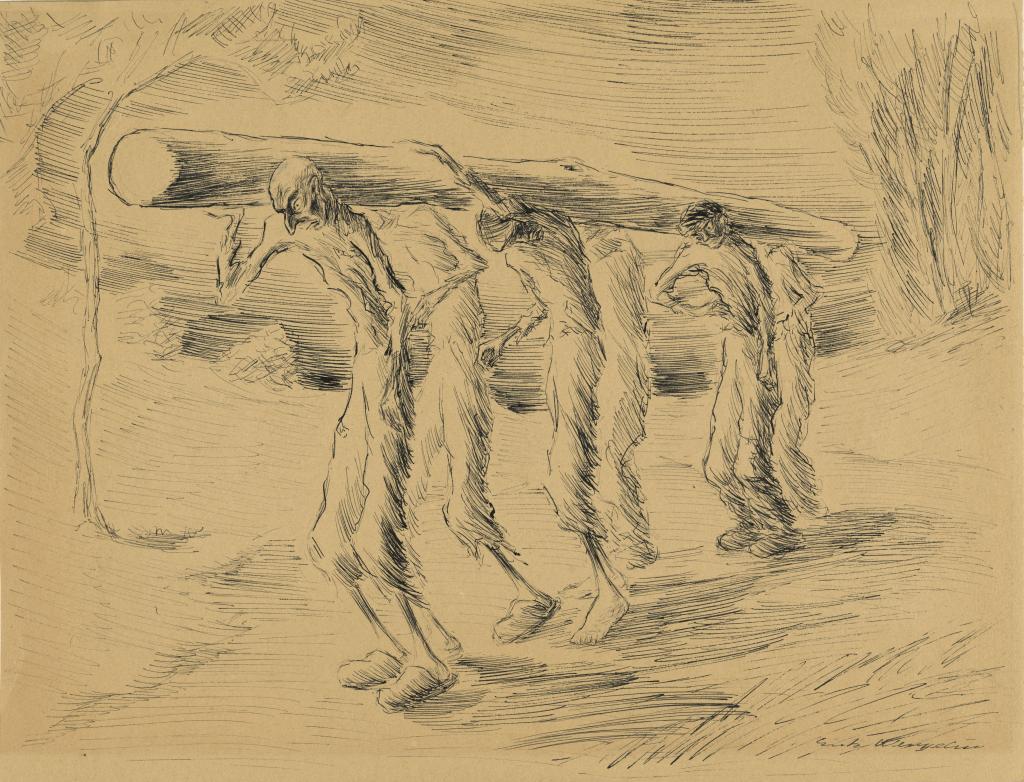

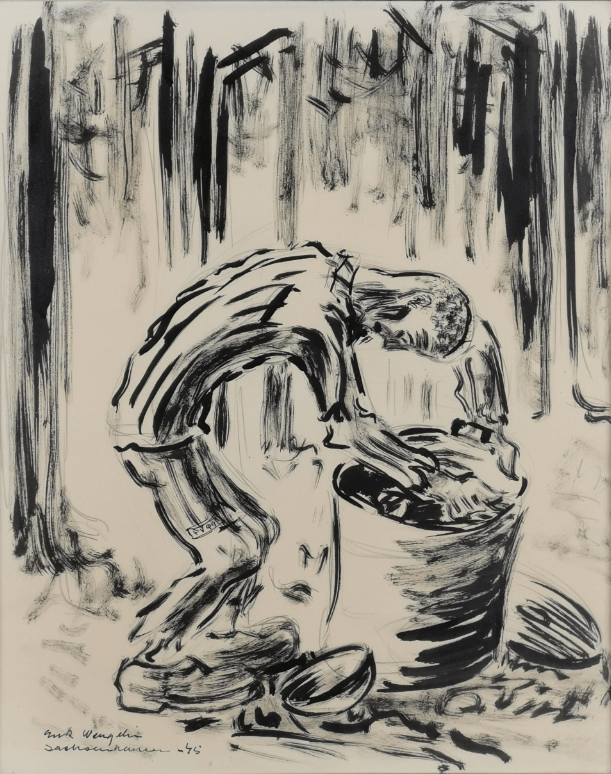

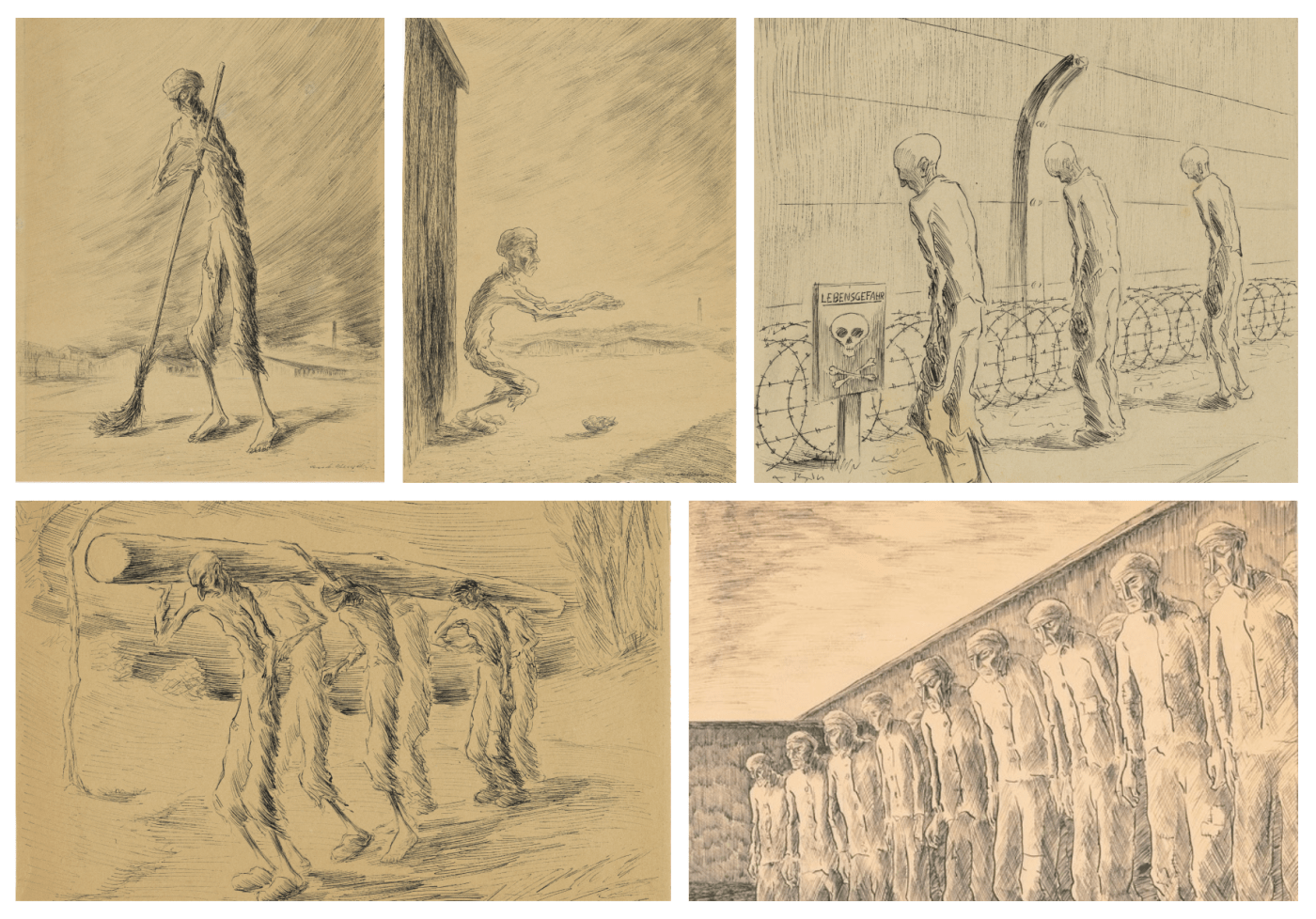

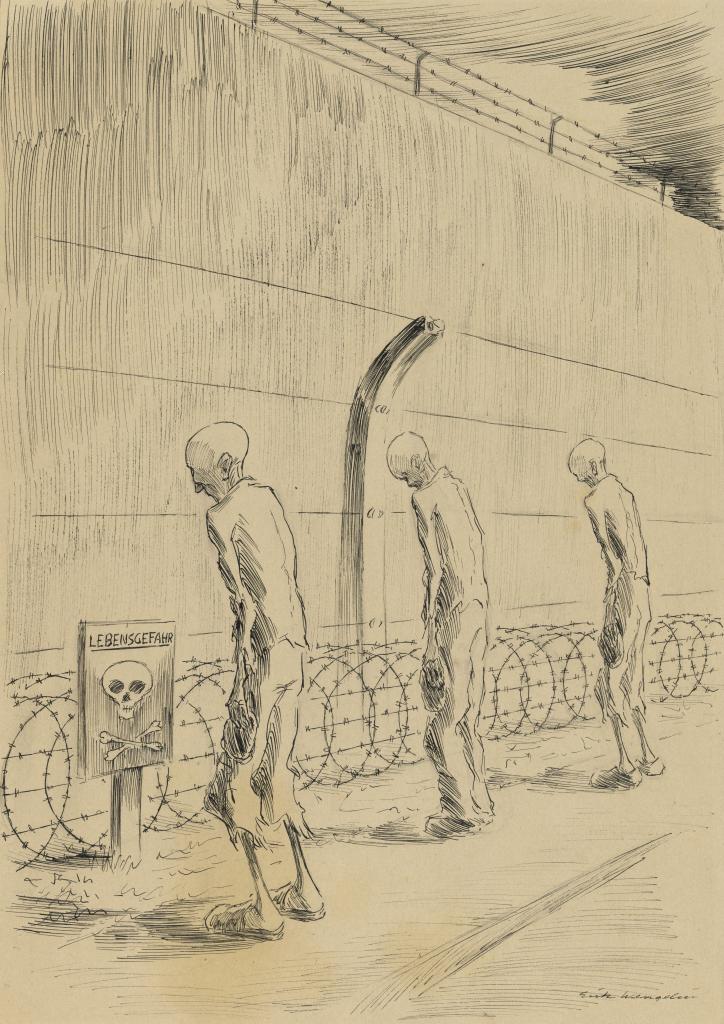

Erik managed to survive the cruelty and harsh conditions of the camp. He remained in Sachsenhausen until he was liberated at the end of the war. In 1945 he created a collection of drawings depicting his experience at Sachsenhausen. For these he used pen over pencil on vellum paper.

“The brutal reality is rendered in line and with nerve, with great contrast between white and black, while the perspective is crudely chopped” (Frihåndstegning, Tom Teigen, 1992, p. 146).

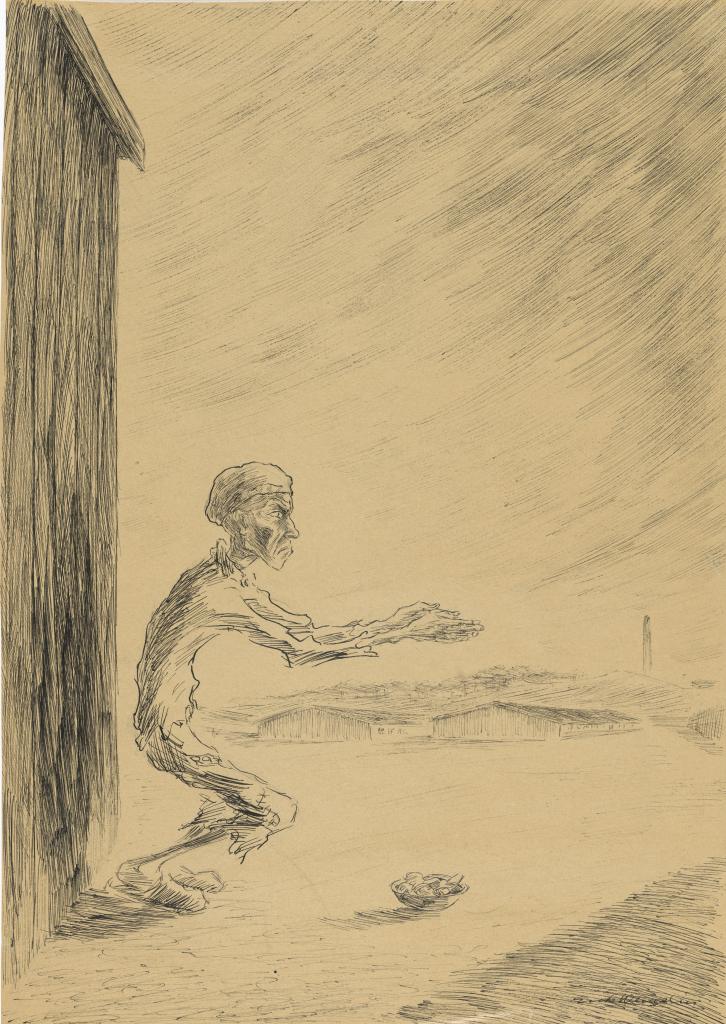

“Appeal” – A contemporary depiction from Sachsenhausen by Erik Wengelin. Verses taken from Carl Jakhelln’s poem “After the appeal”.

“Thirty thousand shadows stood,

silent and lined up in a row,

shadows created by flesh and blood

which is easily broken.

Slave, you will be killed if you don’t keep the beat!

You will be crushed by my heel if you do not respect power!”

“At the gate” – A contemporary depiction from Sachsenhausen by Erik Wengelin. They just stood there, in scorching sun or in rain or freezing cold, until finally the Lagerführer saw fit to receive them to pass the final verdict.

The following Wengelin drawings were found in the estate of Viggo Bredal-Hansen (Heirung) (1915–2011), prisoner at Falstad in the spring of 1942.

In 1947 Erik Wengelin exhibited his Sachsenhausen drawings at Sæbbø A.S. Two Norwegian newspapers published articles about the exhibition:

Moss newspaper (19 May 1947): “The drawings give a picture of what the prisoners there had to go through. You can’t call such motifs “pleasant”, but it can be useful in many ways to keep in mind what happened in these years. It can keep healthy and positive resentment alive, without nurturing hatred.”

The Democrat newspaper (8 October 1947): “The painter Erik Wengelin has collected a lot of impressions from his stay as a Gestapo prisoner in Sachsenhausen, which he has shown in his art. In the five pen drawings he has done, he has depicted in an equally eloquent and realistic way the life of blood and crime that the prisoners there had to submit to. Wengelin can be pleased to have garnered great recognition for his drawings and can therefore refer to references from the best connoisseurs of art. Proof of this can be found in the fact that the National Gallery has purchased some of his works. Wengelin stays in Fredrikstad these days, so there will be an opportunity for our many art lovers to both see and purchase from his production.”

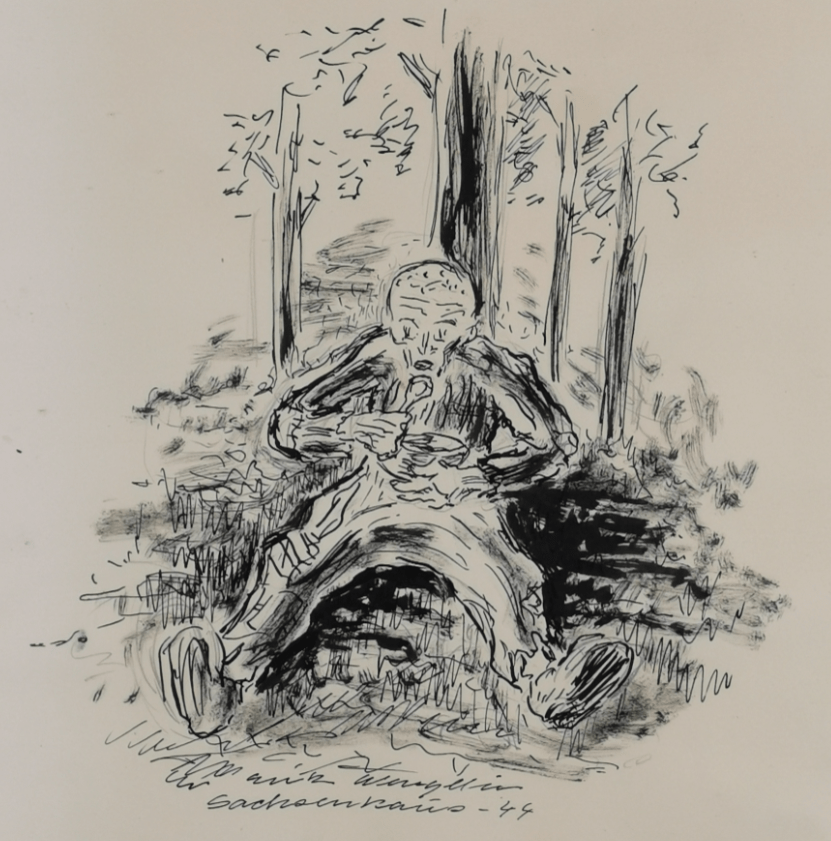

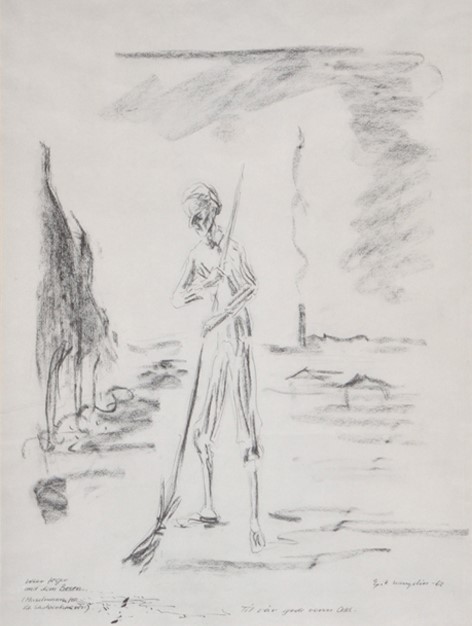

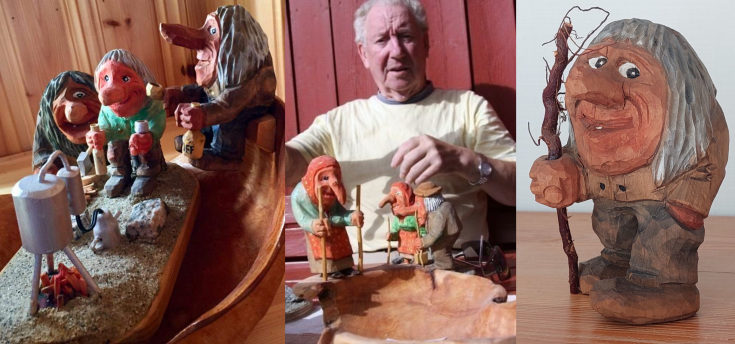

There is evidence of his work up until 1962. He sketched the following image with the title: “Wier sweeping with the broom (Muslim man from Sachsenhausen contentration camp) with a dedication: Til vaar gode venn Odd (To our good friend Odd).

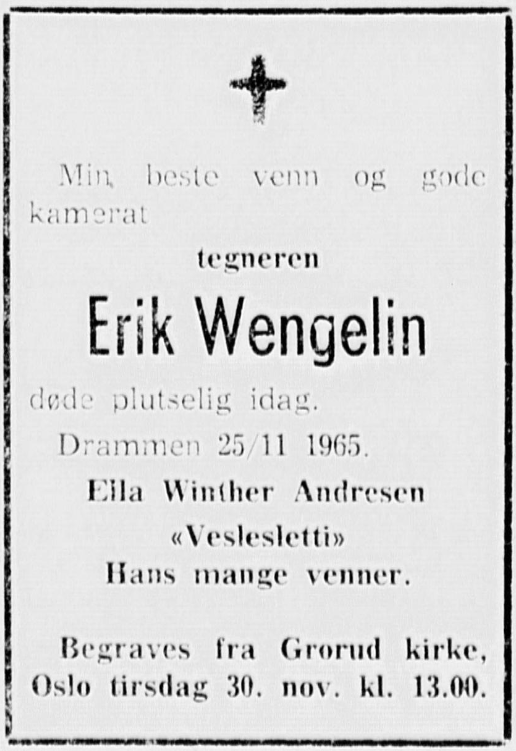

On 25 November 1965, Erik Wengelin passed away in Drammen after suffering a heart attack. He was 58 years old.

The following was published in the newspaper Friheten (The Freedom) on 27 November 1965:

Erik Wengelin is dead

“A sad message reaches us, Erik Wengelin has died. Wengelin had many acquaintances from a wandering life. He was a wandering soul, artist and communist, friend of people and friend of animals.

At a fairly young age he joined the communist youth movement and the party and was actively involved in all kinds of activities. Then came the occupation and he ended up like so many others in Sachsenhausen. Freedom’s readers will remember his account yesterday of his visit to Sachsenhausen on the 20th anniversary of the liberation of the camp by Soviet troops. It was illustrated with one of Wengelin’s poignant drawings from Sachsenhausen, the drawing has been given a place in the National Gallery. He himself came home as a physically scarred man.

It was once again a wandering existence. He participated with great energy in the War Invalids Association and its work. For many years he stayed at Bereia, the home for war invalids. Now quite recently he got himself a dormitory flat in Drammen, which has always been a point of reference for Wengelin. It was the first time he got his own flat with a deposit, he said. Now he needed to calm down, and he signed up to work in the party again. But then it won’t last that long. Death came suddenly.

Wengelin’s drawings of the Muslims in the Nazi concentration camps were poignant. As mentioned, one has been given a place in the National Gallery. One of his posters has also been placed in a museum in Moscow. A close friend of his writes to us: One of our dear old comrades has passed away. His greatest joy was making others happy, I would especially like to mention his joy at being able to help children and animals. Several times he spent his last money to buy food for animals he thought were starving. Many are comrades from the concentration camp, from the party and not least from the circle of war invalids who feel a void after their friend Erik has passed away. Peace to his memory.”

About the Author

For more articles visit Dayne’s Discoveries Blog, browse our online shop, or contact us to share information, stories, or photographs relating to Erik Wengelin.

Leave a comment