The medieval Baldishol tapestry, from 1180, is a national treasure familiar to most Norwegians.

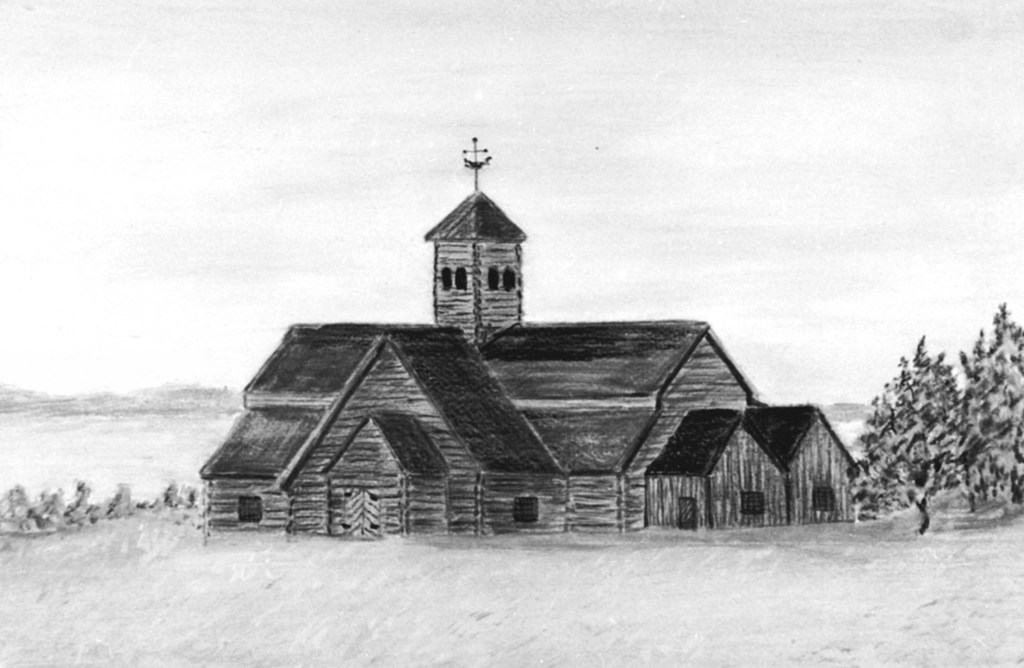

The origin of the tapestry is unknown. It’s name comes from the 17th century Baldishol church on Nes in Hedemark, Norway where it was discovered. In 1879 the church was demolished and many materials and fixtures were sold at auction. The Kildal family on the neighboring farm to the church acquired some of the objects and kept them on the farm.

A relative, Louise Kildal, who was visiting a few years later found among church pictures and some church spiers, a dirty, old rag, full of clay, which had been lying under the footstool of the organist as protection against the draft. Louise Kildal took care of the rag, washed and cared for it. Out of the dirt came a tapestry of colours. She hung it in her living room where it was discovered by the director of the Kristiania Museum of Applied Industry, HA Grosch, who purchased it and made sure that the tapestry was transferred to the museum.

When it was studied closely, it was dated as sometime after 1180, and likely the mid-1200s. The tapestry measures 118 x 203 cm and is torn at either end, indicating it was most likely part of a larger work, perhaps the whole 12 month calendar year. The preserved part depicts April and May. In all likelihood it was a long picture frieze, a beautiful tapestry in the Romanesque style. Historians place it stylistically as late Romanesque. The Baldishol tapestry is unique in Norwegian history as the only remaining tapestry from the Romanesque art period which is the art of Europe from approximately 1000 AD to the rise of the Gothic style in the 12th century. In European history, it is also very rare being among only a handful of Romanesque tapestries still existing (Source: AbsoluteTapestry – Baldishol).

Its strength and clarity of colour and the total wholeness of its drawing and composition gives us a compelling image. With some knowledge of Romanesque art we can imagine how the other months might have been depicted. If we imagine a tapestry of twelve months length it may have been woven for Hamar Cathedral that was completed around 1200 (Source: A Synopsis of the History of Norwegian Tapestry – and Some Thoughts about Tapestry Today).

The tapestry technique employed is ”stepping” and ”dovetailing” throughout. This is a quintessential mediaeval method that became the cornerstone of the Norwegian tapestry tradition. The Baldishol warp is made of two ply, coarse Spælsau wool, with approximately 3.5 threads per centimeter. Spælsau is the name of a breed of sheep which many believe to be the original breed of sheep in Norway. The weft is thin wool and linen. This makes a ridged surface that brings out the drawing and emphasizes the technique.

The tapestry has remarkable high colour intensity. Made with vegetable dyes, it is outstanding that the colour has maintained so much of its original quality. The blue and red colours are believed to be almost the original intensity, whereas the green and yellow have mellowed with time. The white colour is bleached linen and maintains it’s near pristine crispness.

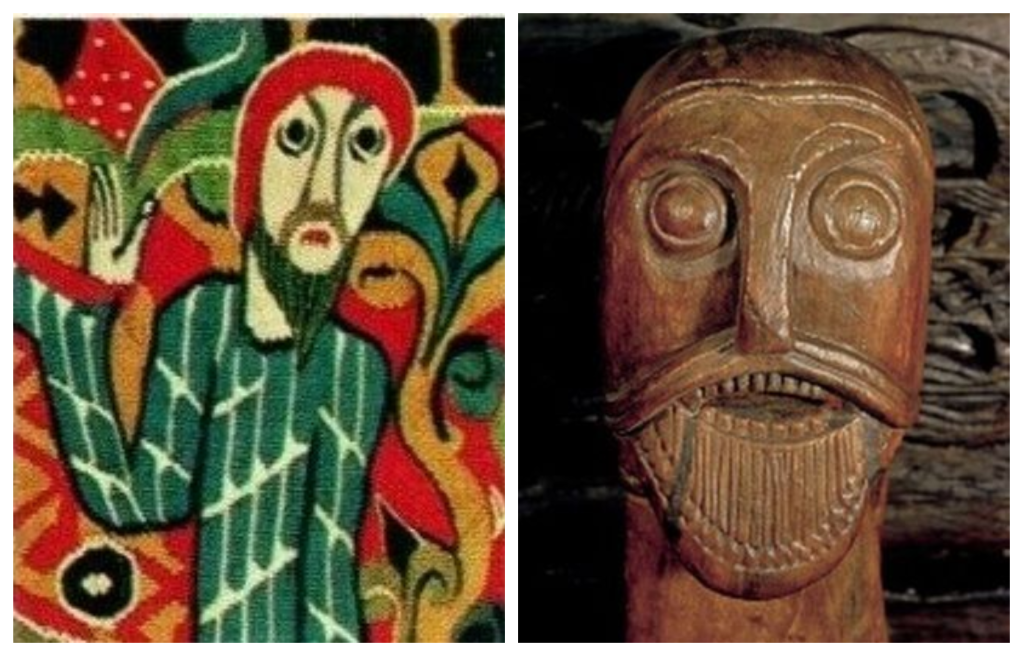

April is depicted by a bearded man in a long robe next to a tree with birds that is thought to symbolize the arrival of birds with the coming of Spring. May is shown with a rider in armor which is thought to symbolize that one can now ride on the ground.

The figures in the two fields are placed under their respective flattened round arches with partially illegible month names as inscriptions. They are separated by columns of different design. The legs of the man in the coat in April protrude below the image field in the same way as the front legs of the horse. Similarly the rider’s helmet protrudes just above the field. This shows that the artist has felt great freedom towards the motif.

One interesting observation is that the face of the bearded man resembles the design of the faces carved on the cart found in the Oseberg ship burial which is believed to be built before 800 AD. Similarities can be seen in the rings around the eyes, long nose with lines linked to eyebrows and the pointy beard around the mouth.

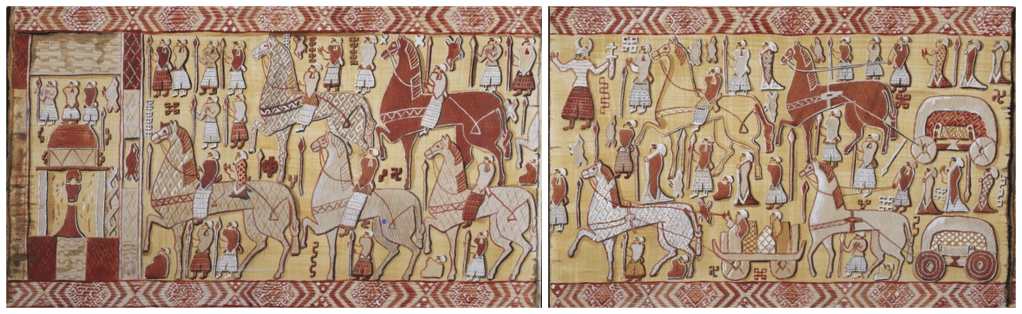

Although the Baldishol tapestry is widely documented as the earliest medieval tapestry of Nordic origin, that title belongs to the Oseberg tapestry (dated to about 834AD) which was created many centuries earlier. Bjørn Hougen wrote the following about this find in 1940, “Tapestry and woodcarving, in these two words lies the starting point for an entirely new perspective that the Oseberg ship has given to the art history of the Viking Age.” (Source: A Synopsis of the History of Norwegian Tapestry – and Some Thoughts about Tapestry Today).

The Oseberg tapestry is a fragmentary tapestry, discovered within the Viking Oseberg ship burial in Norway. The tapestry is in bad condition and was probably a part of the funeral offering in the ship burial. Its decay meant it took several years to extract.

The fragments of the tapestry feature a scene containing two black birds hovering over a horse, possibly originally leading a wagon (as a part of a procession of horse-led wagons on the tapestry). Anne Stine Ingstad interprets these birds as Huginn and Muninn flying over a covered cart containing an image of Odin with a horned helmet, drawing comparison with the images of Nerthus attested by Tacitus in 1AD. It is very interesting to note that Odin is wearing a horned helmet, as the viewpoint has long been that, historically, Vikings never wore horned helmets. Anne Stina Ingstad wrote that the textiles found in the burial chamber of the Oseberg ship are “without comparison in Nordic pre-history.” She points out that the tapestry fragments are by far the most important examples of the collection.

The tapestry was one of a number of textile remains found during the Oseberg ship excavation in 1904, near Tønsberg in Vestfold. Other finds included rolled-up rugs, tapestries, curtains. Most are embroidered with mythological and battle scenes. There was no representation of the ships owner. Graves have shown that the Vikings loved the expensive fabrics, which were acquired through trade. Their clothes were decorated with delicate embroidery, sometimes in gold thread.

Both the Oseberg and Baldishol tapestry are stylistically similar to the world’s most famous Medieval tapestry work, The Bayeux Tapestry, depicting the Norman Conquest of 1066. The Bayeux carpet, on the other hand, is an embroidery that describes the Norman invasion of England, and not a fabric.

Norway is fortunate in having tapestries from different periods in its history. Through these we can learn a great deal of social and art history, and last but not least, women’s history.

Today, the tapestry is on display at the Norwegian Museum of Decorative Arts and Design in Oslo (Kunstindustrimuseet). It is considered one of the most valuable artifacts in the museum and is housed in a dark room under climate control. This brilliantly colourful tapestry is in remarkable condition considering its history.

The Baldishol Tapestry is recognised all over Scandinavia and by those who are versed in Nordic textile traditions. It has been replicated many times and will continue to be a fascinating part of Norway’s history, enjoyed by future generations.

About the Author

For more articles visit Dayne’s Discoveries Blog, browse our online shop, or contact us to share information, stories, or photographs relating to the Baldishol tapestry.

Leave a comment