Whilst conducting family history research in my early 20s, one of my main goals was to trace my European ancestors back to their respective countries and identify the reasons why they left their home land and traveled so far to settle in South Africa. Even though my surname (Skolmen) is Norwegian, having grown up in East London I had an interest in establishing how my ancestors ended up in this small city. This is where my German heritage journey began…

This article details the family stories of the Bauer and Rüffer German immigrant families who arrived in East London, South Africa in 1878.

Life in Germany

Joachim Schubert provides some interesting insight about what the lives of the Bauer and Rüffer family in Germany might have been like:

“Hermann and Maria Bauer were from Caternberg in Westfalia (Westfalen in German). Nicolaus and Eva Rüffer were from Ottekampshof, also in Westfalia.

I found Katernberg, a part of the City of Essen. Essen was not in the Prussian Province of Westfalia, but just on the other side of the border with the Prussian Rhineland Province. It was likely part of the larger historical area of Westfalia, though. After World War 2, the old Prussian provinces were dissolved and a new ‘State’ was formed out of the Northern Rhineland and Westfalia to become “Rheinland-Westfalen.”

Katernberg and Essen are located in the middle of the Ruhr Industrial area in Germany, a large conglomeration of cities. Katernberg can be found at 51°29’49.0″N 7°02’56.0″E.

Ottekampshof was a ‘colony’ or a housing estate for one of the mines in Katernberg. There is still a street in Katernberg called Ottenkämperweg. The original settlement was named after the farmer who sold the land used to establish the settlement.

Chances are therefore, that the Bauer and Rüffer families already knew each other in Germany. If not, they would have got to know each other en route to South Africa.

The area around Katernberg was undergoing major development just at the time the Bauer and Rüffer families left. Hermann and Nicolaus were both ‘Landarbeiter’ i.e. agricultural labourers without their own land. Maybe they were unable to find jobs in the agricultural sector and did not want to work in industry. Or they could have moved into one of the new industrial centres from elsewhere in the search of jobs, found that this was not a good way of life and then decided to leave. Either way, it is interesting that they left at a time when there must have been a lot of employment opportunities in the new steel works, etc.”

To this day, I have not managed to trace the families in Germany which they left behind. My German family tree stops at these ancestors who immigrated to South Africa. I have attempted to obtain local church records in Germany, however, many of these were destroyed during World War 2.

Below is an interesting cardboard German photograph that I found in my paternal grandmother’s old wooden sewing box. It displays two German girls (possibly twins) and confirms the link between my German ancestors and Katernberg.

There must have been something to motivate their desire to leave the comfort and familiarity of cobbled stone villages, farms and established ancient communities with their social structure, music, literature and cuisine for the unknowns of wild Africa on the other side of the world. One explanation could be the opportunity to own land as part of the South African Governments immigration scheme.

South African Immigration Scheme

The Kaffraria Germans are members of three very different groups that settled in British Kaffraria (the southeastern part of the Eastern Cape in present-day South Africa) in the 19th Century:

- The German Crimean Legion, 1856

- The Colonists of 1858 and

- The Colonists of 1877/78

The Bauer and Rüffer families were part of the colonists of 1878. The following extracts provide some insight into the immigration scheme for the 1878 group of settlers. The information is taken from a thesis entitled German Immigration to the Cape (Section XXI: German Immigrants 1877-78 and 1883, pg. 281-293) written by E.L.G Schnell in 1952 as part of his Doctorate in Philosophy at Rhodes University in Grahamstown:

“A number of years elapsed before the Government again embarked on an extensive scheme of immigration. The Surveyor-General’s Report issued in 1876 showed that there was still a “considerable extent of unalienated Government land in various parts of the Colony, specially adapted for agricultural purposes and valuable as a means of attracting immigration”. Hence on the 28th June, 1876, the House of Assembly adopted a motion expressing its opinion that such land should be surveyed, and that arrangements should be made to secure suitable immigrants from North Europe. In addition, the House defined generally what type of settler should be introduced. The Commissioner for Crown lands, Mr. John X. Merriman, thereupon entered into an agreement with William Berg to introduce a number of immigrants from Germany and Scandinavia, the contract being signed on the 17th August, 1876.

As on former occasions, William Berg was to co-operate with Measrs. J. C. Godeffroy & Son of Hamburg, and was to conclude arrangements for introducing 1500 statue adults (two children under twelve to count as one individual). The Immigrants were to consist of Norwegian, Swedish and German peasants who had been employed in agricultural pursuits and were of respectable character. As a rule, only married couples with their children were to be accepted; young women could come out if under the care of guardians, and a certain proportion of “single” men was allowed, though married couples were preferred. The age limit was fixed at fifty years.

As soon as the contract had been drawn up, William Berg communicated with Measrs. Godeffroy & Son who, as on the former occasion, appointed sub-agents to collect the immigrants and forward them to Hamburg.”

Voyage to South Africa

The later German settlement scheme was much smaller in scale than these first two schemes (Source: Gisela Lesley Zipp, A History of the German Settlers in the Eastern Cape, 1857 – 1919 , pg.12, 2012).

“Altogether, ten ships were chartered for this group of settlers – the “La Rochelle”, “Fedrasa”, “Wandrahm”, “Godeffroy”, “Caroline Bahn”, “Sophie”, “Adele”, “Papa”, “Saturnas” and “Uranus”, and they brought out about 1900 souls, as well as another thirty-five who paid their own passage. A number of these were, of course, Scandinavians but undoubtedly the great majority were Germans. Unfortunately the place of origin is not always stated, so it is impossible to determine the exact proportion of Germans.

A doctor was to be carried on every ship having more than a hundred immigrants; if necessary, the immigrants were to be kept on board the ship for a period of eight days after the arrival at the port of destination. In return, the contractor was to be paid £15 for every immigrant introduced to the Cape and approved of by the Immigration Board; for the passage of the doctor the sum of £30 was to be paid” (Source: E.L.G Schnell, German Immigration to the Cape, pg. 282, 1952).

As the continuance of the Xhosa Wars made it inadvisable for the Government to send any more Germans to the Eastern Cape, it was decided to settle those who were still to come in the Western Province. Hence the “La Rochelle”, “Pedram”, “Sandrahm”, “Godeffroy”, “Saturnas” and “Uranus”, with a total of about 1040 passengers, did not proceed to East London, but landed them at Cape Town. A few of those subsequently proceeded eastward to join their compatriots at East London, King Williams Town and Keiskammahoek, but the majority remained in the vicinity of Cape Town.

”Only a small portion of the 1877/78 German immigrants ended up settling in the Eastern Cape – most settlers, including the Philippi Germans, settled in or around Cape Town. (Source: “Die Kaffrariadeutschen“, written by Rolf Grüner for the Special edition of ‘Lantern’ published in February 1992).

Of the ten vessels which brought out the immigrants, only three proceeded directly to East London, the “Caroline Bahn”, the “Sophie” and the “Adele”, while the majority of the passengers of the “Papa”, after being transhipped to the “Asiatic”, were also sent to East London. In addition, sixteen immigrants of the “Wandrahm” elected to go to East London and were sent there. Althogether about 700 individuals proceeded to the Eastern Province (Source: E.L.G Schnell, German Immigration to the Cape, pg. 284, 1952).

An article in the East London Daily Dispatch on 5 Nov 1877 provides some insight into the voyage from Germany and arrival of the immigrants onboard the ship “Sophie”: “The Sophie containing the second lot of German Emigrants for this Port arrived yesterday. Her passengers are being landed today and will be located on the East Bank temporarily. On the voyage out, one man jumped overboard and was drowned, but there were no other deaths.”

The Bauer and Rüffer families came over on the Hamburg steamer “Papa” which arrived at East London on 25 July 1878. In 2014, Patti Putter shared the following newspaper clipping on RootsWeb. It contains information about the 1878 German Settlers that came over on this specific ship. She mentioned that her great-great grandparents came out with this group of settlers and that she had found the newspaper clipping in an old family bible. The content of the article is provided below:

East London – Wednesday, July 25, 1928

FIFTY YEARS AGO

The German Immigrants of 1878

Fifty years ago to-day there arrived at East London, after a six weeks’ voyage from Europe, a party of 272 immigrants – men, women and children – who came as far as Cape Town in the Hamburg steamer “Papa” and were then transshipped to the mail steamer “Asiatic,” which brought them on to their destination. Their coming-out was in pursuance of the Cape Government’s policy of increasing the white population on the frontier and so forming a rampart against incursions by the native tribes. The settlers are sometimes referred to as the German immigrants, but though the majority came from Germany, there were a number from Denmark, Switzerland, Austria, and Poland. This party of immigrants is, of course, not to be confused with the immigrants of the German Legion, who arrived 20 years earlier.

Forty-seven families – forming the greater portion of the immigrants – were given ground at Paardekraal, Kwelegha, where the land had been cut up into small holdings. The head of each family received an advance of £9 in cash from the Government and also two bullocks, valued at £9 each, the loan and the price of the beasts having to be repaid in due course.

For their land they were charged an annual rental of ten shillings per acre, and they had grazing rights on the Paardekraal commonage. In spite of their frugality and industry, they had a very hard struggle at first, and most of them in the course of a few years had moved away from their original settlement, but not many of these went farther than the boundaries of the East London and Komgha districts. As will be seen from the list below, the majority of the names are well known in this part of the country. Among the very few immigrants who still remain in the original locality are Mr C.A. Schafli, of Cintsa, and his brother, who were small children when they arrived here from Switzerland fifty years ago.

The list of passengers of the ‘Papa’ on March 31, 1878 (Source: Hamburg Ship Lists, 1878, Fol. 111-118 – Archive of the Hanseatic City of Hamburg) provides further information about these two families:

Bauer, Hermann (born in Hanover, Germany), agriculture worker (age 28). Katernberg (Westfalia), with wife Marie (age 21 – Nationality British) and Marie (below the age of 1).

The surname Bauer is of German origin, meaning “peasant” or “farmer”. ”It is interesting to note that there were seven Bauer Legionnaires who came out in 1857, two Bauer families with the 1858 Settlers, and then Herman Bauer’s family with the 1878 lot. Which means there are quite a lot of Bauers’ in the East London area.” (Source: Colin Levey).

Rüffer, Nicolaus, agricultural worker (age 35). Ottekampshof (Westfalia), with wife Eva (age 32) and Gertraude (age 8), Anna (age 6), Catharina (below the age of 1).

The surname Rüffer is of German origin, it was a baptismal name ‘the son of Rudolph’ from the nickname Rolf. In England, Rüffer came from the Old English word Hrof and was given to people responsible for roof repairs. The surname could also be of German-Jewish origin.

Arrival in East London

“The immigrants were not required to refund the passage money, and on landing were free to accept engagements as they chose. If they wished, they were at liberty to take up Crown land (at least twenty acres for each adult) at the rate of ten shillings per acre, which was to be paid for in ten yearly instalments of one shilling per acre.

The Government was prepared to convey immigrants from the port of arrival to their locations; it would advance money for the purchase of seeds and agricultural implements and would charge no custom duties on personal luggage, and, in addition, it was prepared to issue rations” (Source: E.L.G Schnell, German Immigration to the Cape, pg. 282, 1952).

Being farmers, both the Bauer and Rüffer families decided to take up Crown land. The following extracts outline the terms under which immigrants could obtain land.

“In practically every case, the arrival of a shipload of immigrants was advertised in the Government Gazette and persons wishing to secure the services of immigrants were asked to communicate directly with them or with the Immigration Board at Cape Town.

As it was found necessary to define the conditions under which immigrants could obtain land more precisely, the “Agricultural Immigrants Land Act”, No. 10 of 1877, was passed and published just prior to the arrival of the first shipload of immigrants. The Act laid down that Agricultural Immigrants could obtain land on the following conditions. In the first instance, the land was to be leased for ten years during which an annual rent of 10 Shillings per annum. It must be noted that nothing was said in the contract between Merriman and Berg about the payment of quitrent; this, as will be seen subsequently, caused difficulties.

Another clause stipulated that the lessee should erect a dwelling house of the value of at least £20 on his land, and that after the expiration of the two first years, he should cultivate at least one acre of every ten acres leased.

The terms granted to these immigrants were extraordinarily favourable; the passage was paid for; they were free to accept whatever work they wished; they were granted every possible assistance, if they decided to go farming – and most important of all, the price of the land was much lower than that paid by the immigrants of 1858″ (Source: E.L.G Schnell, German Immigration to the Cape, pg. 283, 1952).

The following extracts describe how these settlers were processed by the Immigration Board upon arrival in East London:

“At East London, the Immigrants were interviewed by an Immigration Board, consisting of the Magistrate, A. Orpen, Captain E. Brabant and A.E. Murray, the Government-Surveyor, with the Contract before it, this Board examined the newcomers and determined whether the Conditions had been complied with or not. When there was an evident breach of the contract, the immigrants were rejected, as was done on the 27th August, 1877, when four of them, one a painter, another a carpenter, and two locksmiths were not accepted, as the contract stipulated that the immigrants should be agriculturalists.

Occasionally the Board found it rather difficult to come to decisions, for sometimes men appeared before them, who though not actually agriculturalists, had been employed on farms and knew something about the work. As a rule, these were passed.

Another matter which the Board found necessary to report was that the proportion of single men introduced by the “Sophie” was too high, i.e. more than 10%, eighty-nine instead of sixty-seven. Hence it recommended that only the passages of the lower number should be paid.

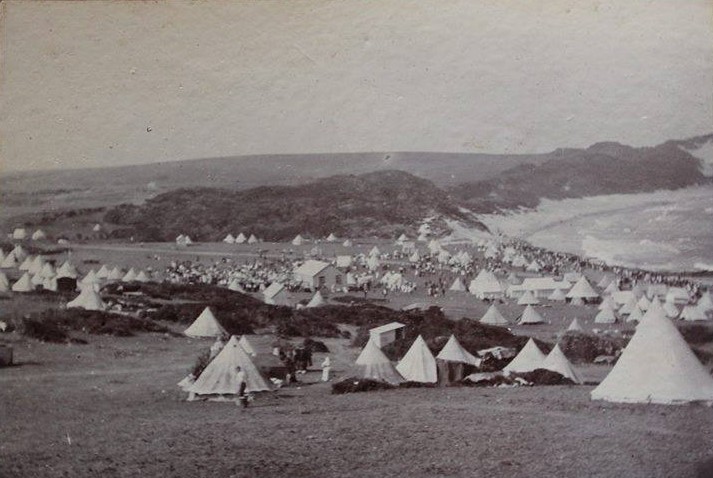

When the Immigrants had been accepted, their names were entered into the “Nominal Roll of Immigrants”. The Immigration Board seems to have been generally responsible for the reception of the Immigrants, and as a preliminary measure, housed them, either in tents on the eastern side of the Pier, or when there were not enough tents, in warehouses at the railway jetty.

According to Nicolaus and Eva Rüffer’s daughter, Luise, there was no shelter when her parents arrived in East London, and so they had to clear a patch in the long grass and then gather the grass together on the edge of the cleared patch and tie it in the middle to form a “hut”.

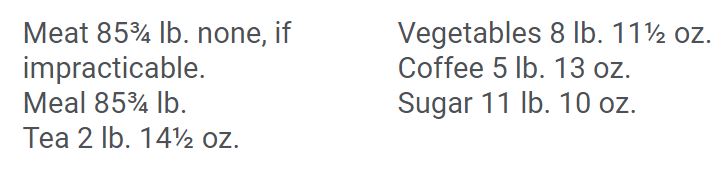

From the time of their arrival, the immigrants were supplied with rations for which, however, they had to pay, if not immediately, at least subsequently. The amount issued is illustrated by the following specimen of rations drawn by a family consisting of three statute adults, that is, probably the father, the mother and two children:

In addition, tins of milk were issued to them, apparently on no fixed scale, but as required. When the immigrants did not procure work locally, but elected to take up land, rations were issued to them for a month at the following scale:

Although the Immigration Board was responsible for receiving and settling the Immigrants, the greater part of the work was done by Captain von Linsingen, an ex-Legionary, then in the Railway Department, and his subordinates. He received the immigrants, supervised their encampment at East London, made himself responsible for seeing that they were rationed, and in every way did what he could to help his compatriots. His help was highly appreciated by the Immigration Board, especially as no member of the Board could speak German sufficiently well to do the work accomplished by him.

When the Germans arrived at East London, the last of the Xhosa Wars was in progress and made it difficult, if not impossible, to settle them at the locations intended for them. The Xhosa Wars refers to a series of nine wars or flare-ups (from 1779 to 1879) between the Xhosa Kingdom and European settlers in what is now the Eastern Cape in South Africa. These events were the longest-running military action in the history of African colonialism.

As some action had to be taken in the meanwhile, the men, or rather some of them, were approached and asked whether they had been soldiers in Germany. On their replying in the affirmative, they were promised 6 shillings a day as pay, if they enlisted. Numbers accepted and saw service against the Natives, while their families remained at the Immigration Depot at East London.

When the country was more stable, Germans that applied for farming land, were settled. These later settlers largely did not settle in the same places as the previous German settlers. The majority settled at Kwelegha, Lilyfontein and Paardekraal, though a few went to Keiskammahoek, Modderfontein, Komgha, Nahoon Mouth, Kei Road, Fort Murray, Amalinda, Cambridge, and King William’s Town. Only three of these locations showed any overlap at all between the 1857-58 settlements and these later settlers, namely Keiskammahoek, East London, and King Williams Town. (Source: A History of the German Settlers in the Eastern Cape, 1857 – 1919, pg. 12, 2012). The other settlers preferred seeking work for themselves, many being successful in finding suitable employment.

Building a new home

The Bauer and Rüffer family settled in Upper Kwelegha along with the following German settler families (Source: Deutsche in Kaffraria. 1858 – 1958. Published by: J.F. SCHWÄR and. B.E. PAPE, pg. 64):

- OBEREM [no initial provided]

- H. BAUER

- N .LISS

- W. HOFFMANN

- F. SPRINGER

- W. DE BEYER

- C. KRETSCHMANN

- N. RÜFFER

- J. HEGER

In accordance with its promise the Government transported them and their families by ox wagon to the locations chosen by them.

Each family was allocated a small holding to build a house and start farming the land. The Bauer homestead was located on Lorainne farm in the Bluewater district and the Rüffer homestead was located on Rooikop farm in the Mooiplaas district (apparently, the foundation and broken stone walls still stand).

The image below shows where the farms were located:

“Those who needed assistance, on signing a promissory note, were helped to procure seed and agricultural implements. Apparently the accounts were sent to the Magistrate at East London, for a large number, varying in amount between £3 and £9, and bearing dates between September, 1877, and January, 1879, are extant. The following is a typical example:

Though helped to this extent, the immigrants were usually not supplied with a plough and oxen, but as these were indispensable, they appealed to the Magistrate at East London to let them have one plough for every three or four families and two oxen for each family to enable them to plough their lands. The reason they assigned for this request was that they found it quite impossible to pay the price asked by the farmers already established in the neighbourhood of their locations, who charged 10 shillings (later 20 shillings) for ploughing a small plot of ground, usually about one-third of an acre.

The result was that the Immigration Board allowed each immigrant to purchase two oxen, provided that Mr. Krohn, who had been appointed Superintendent of Immigrants approved. In addition, he was to find out how many ploughs were required and was to make arrangements for supplying the Immigrants with these.

Altogether seventy-eight immigrants procured oxen and ploughs in this way; the initial outlay varied between £17 and £24 for which they signed promissory notes.

The immigrants now had all that they required. “In a most praiseworthy way” they set to work, their land was brought under cultivation and everything seemed suspicious for the future. Unfortunately for them, drought set in; their crops failed and the hard work done by them had been in vain.

The Devastation of Drought

Many of the immigrants were in danger of actual starvation; the money advanced to them had all been spent on seed, ploughs, etc. and for food, and they had to appeal for help. In forwarding their request, Hughes, the Government official to whom they had turned in the first place, said, “The results of their labours, as shown by the present state of their gardens, is conclusive as to their having worked hard during the short time that they have been out.

A newspaper article from the East London Daily Dispatch dated 12 Oct 1878 provides some further information on the hardships experienced during the German settler’s first few months in South Africa:

”GERMAN IMMIGRATION – A large number of these immigrants from the various locations in this District, interviewed the Local Immigration Board yesterday, with a view to representing the almost destitute condition in which they find themselves temporarily placed. Many we understand are in great want and it will probably be necessary for the Government to supply them with rations for a time until their crops come up.”

Much more deplorable was the account given by the District surgeon, Dr. Hewitt Fayley. “I have within the last few days visited the German Immigrants in this District. The greater number of them appear to be in a very destitute condition. Their crops are not coming up owing to the long drought, and many of them have barely sufficient to keep body and soul together. Hard working, scantily clothed and half starved, they have been reduced to a worse condition than any I have ever seen, even in pauper practice in London… Diseases brought on by want and exposure are rife among them, and unless immediate steps are taken for their relief, many will certainly succumb to their hard life”. Consequently he recommended that rations be issued to them and, in some cases, even wine and condensed milk.

As these reports show, the position was such that the Government could do no other than help. The superintendent procured the necessary supplies and issued them in bulk to the immigrants, who in return gave promissory notes for them. Meat, meal, coffee and salt were the usual items issued, though in many cases compressed vegetables and lime juice had also to be served out to them, as scurvy had made its appearance.

This helped them for a time, but as there was little prospect that the Germans would be firmly established for some time to come, James Ayliff, the Magistrate at East London, considered it advisable for the able-bodied men to obtain temporary employment upon public works; their families could, if they wished, remain on their allotments, or could be brought to Panmure.

At the time, a considerable amount of railway construction work was in progress, and on this a number were employed at 4/6 a day. Apparently they were not satisfied with their pay and struck, but as the kind of work they were doing could have been done more cheaply by Native labour, they were given little sympathy and were curtly informed that as they had refused work “at a very fair and reasonable rate, they could not expect any assistance from the Government”. This warning proved effective and a number returned to their work. In the meanwhile, rain had fallen so that their prospects were brighter. Though droughts were mainly responsible for retarding the progress of settlers, another factor to which their difficulties can be attributed was the unsuitability of the land allotted to some of them. Practical experience soon demonstrated that some of the land was useless, with the result that exchanging of land was permitted at the recommendation of Surveyor Murray, who was a member of the Immigration Board. A number of such changes were made at Lillyfontein, Paardekraal and Kwelegha.

“This new group was allocated land closer to East London (in Oberkwelaha, Brackfontein and Lilyfontein). They seem to have been more highly educated and experienced farmers than the first group. Many quickly realised that the land allocated to them – though better than the first group had received – was inadequate. They subsequently left their farms and settled in the local towns or other areas of South Africa.” (Source: “Die Kaffrariadeutschen“, written by Rolf Grüner for the Special edition of ‘Lantern’ published in February 1992).

The next report is dated 21st March, 1881, when the Superintendent of Immigrants in the East London District, now J.N. Hellier, reported that though the immigrants had been brought into dire straights, owing to drought, matters had improved greatly since rain had fallen. “They are,” he said, “in every way settlers, and the major part are very respectable, hard working and thrifty”.

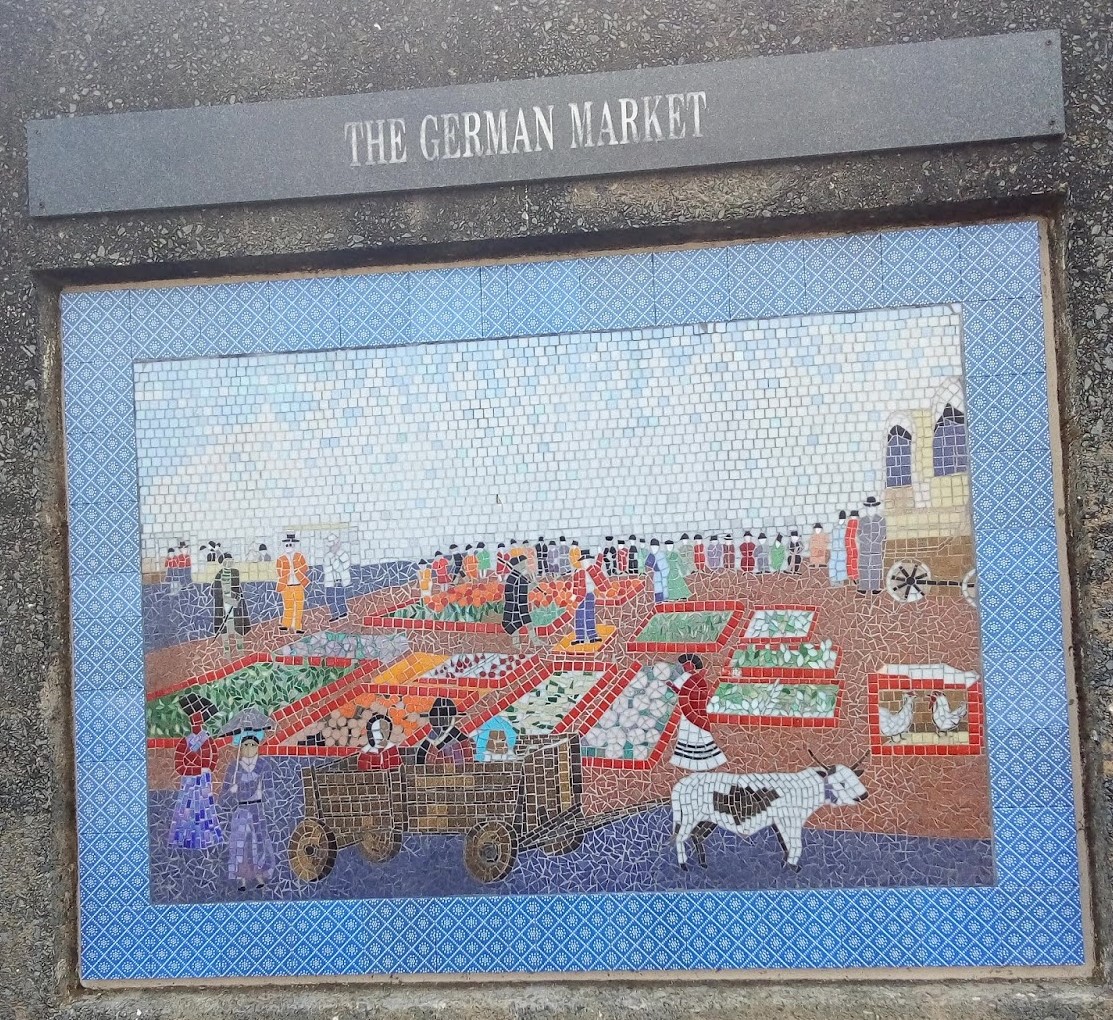

Years passed by and this group of Germans continued to work hard. ”The men worked as farmers or craftsmen in the area and the farmers’ wives traded dairy produce and vegetables at what was then known as The German Market” (Source: A History of East London).

Slowly but surely, their new lives became more stable, and the Bauer and Rüffer families began to grow:

- The Rüffer family had an additional two children in South Africa: Luise Maria Matilda Rüffer (Born 5 May 1887) and August Friedrich Heinrich Rüffer.

- The Bauer family (who were significantly younger than the Rüffer family) grew substantially with an additional six children being born in South Africa: Friedrich Ludwig Hermann Bauer, Friedricha Dorothea Bauer, Friedrich “Fritz” Rudolph Bauer (Born 12 March 1884), Gertrud Marie Bauer, Heinrich (Henry) Hermann Rudolph Paul Bauer, and Ludwig Bauer.

“In 1884 (6 years after arriving in South Africa), a number of the Immigrants interviewed H.H. McNaughton, an Assistant Commissioner of Crown Lands and Public Works, and stated that they objected to having to pay survey expenses and quitrent on their lands. They pointed out that there was nothing in the conditions laid before them, when they emigrated, to warrant their being any obligation to pay; consequently they refused to sign their leases and receive the title deeds to their lands.

The interview proved fruitless, as McNaughton had to explain that the fault did not lie with the Government, which had not authorised the circulars laid before them, but with the immigration agents who had failed to acquaint them with the laws of South Africa referring to land ownership.

Their next step was to obtain legal advice and they consulted Mr. Thomas Upington (16th January, 1884). He made it clear that under Act No. 10 of 1877, an annual quitrent had to be paid after the title had been granted, but he also pointed out that according to the conditions under which the Germans had come, they had been informed that once they had paid for their land it was theirs without further obligation. The only remedy he could recommend was an appeal to Parliament.

This the Germans did; they explained the position and humbly asked that they should not be required to pay either quitrent or survey expense, as they had taken up land under the full belief that neither would be required of them.

A select committee was appointed to inquire into the matter. It found that the conditions laid before the Immigrants contained nothing to the effect that quitrent would be charged, but held that the Clause of the Resolution of Parliament giving Immigrants the option of purchasing lands under the Agricultural Lands Act, made quitrent an obligation. The fault had been committed by the agents, and Parliament was not bound by this.

A year later the matter was brought up again, probably on the advice of Captain Brabant, N.L.A. (a member of the Immigration Board, East London) who was appointed Chairman of a second Select Committee deputed to examine and report on the question.

After hearing the evidence, the Committee considered that though Mr. C. Godeffroy had failed in his duty in not having seen to it that the Germans were fully informed regarding the provisions of the Act, the Government was responsible for the failure “in equity, if not in law”. Hence the Committee recommended that the Government should forego its claim to quitrent on these lands, provided that the purchase price was paid within twelve months of that date.

Parliament acted on the advice of the Committee, and settled the matter finally by the “Agricultural Immigrants Relief Act”, No. 37 of 1885. By this Act, any immigrant who had made the contract with William Berg, or his agents, and had immigrated to Cape Colony, was not required to pay the quitrent and could receive his title deeds as soon as he had paid for the land.

This was the final act of the drama as far as the Government was concerned. The German Immigrants of 1877-78 had been brought out to the Cape, and as many as had elected to do so, were settled on Crown Lands in the East London and Komgha districts. After their initial hardships, they prospered and established themselves as successful farmers.” (Source: E.L.G Schnell, German Immigration to the Cape, pg. 290-292, 1952).

In Nicolaus Rüffer’s Estate File he lists Hermann Bauer and Johann De Beyer as the executors of his will and administrators of his estate and effects, which gives the impression that these settlers stuck together in a close knit community. They were proud of their German heritage and made sure it was retained. “The German School also ensured that the language was kept alive” (Source: A History of East London).

Life went on in East London and the connection between these two German families was further cemented when Friedrich Rudolph Bauer married Luise Maria Matilda Rüffer.

Friedrich and Luise had eight children together, one of which was my paternal grandmother, Eva Hilda Bauer (1918-2005).

Family Stories

Since the Bauer and Rüffer families did not document much of their life, the strongest family stories and memories come from their living descendants. Most notably are memories of Luise Bauer (known as Granny Bauer).

”Luise was definitely a no-nonsense sort of person, who always, until just a few years before her death in 1971, walked great distances, up hill and down dale, to visit friends in the Bluewater district. Her short, plump person was well known to everyone in the area. She wore a small black hat with a turned-up brim on her long walks to visit people and would walk quickly, taking small, fast, short steps. She had grey hair, which was always neatly cut into a short style. I would not be surprised if she cut it herself, or at least got someone in the area to cut it. I somehow don’t think she would have “bothered” with hairdressers. But then, I might be wrong.

Crocheting was her passion and her hands were never idle. Baking really tasty, plain yellowish biscuits was another gift of hers. She would make tins and tins of these biscuits. It appears that sewing was a necessity of life that she never quite mastered. Nevertheless, she hand-sewed all her children’s clothes. Ansie (Ernest) Bauer remembers going to school with “long” shorts with pockets in the vicinity of the armpits. It stands to reason that the other children wore the same type of clothes. School, at Bluewater Primary School, was a luxury. Walking to school, shoeless, was normal, as was helping in the home and on the farm after school. Time to do homework was almost not possible, but somehow they coped. Luise would send tea and sandwiches to the lands for the children, who would be helping there after school, as she knew they would not come home first before going to help in the lands. It was a case of walking from school, stop and work all afternoon, and then continue home in the evenings, possibly to help again in the farmyard.

I recently made contact with my cousin, Yvonne Jordan. She related the story of when she left East London to go and study for higher degrees in Durban: the whole family tried to talk her out of it, with the exception of Granny Luise Bauer, who encouraged her. This is the type of person she was.” (Source: Grand-daughter Phyllis Bennett nee Bauer, 1990s).

”My maternal grandmother, Luise Bauer, lived with us for ten years. Her husband had died before I was born. When she would kill a fowl, she would never use a knife; she would take the fowl by its neck and turn it in a circle until the neck came off. This was a German tradition, and she would enjoy seeing the fowl running around without a head. She would then soak the chicken in a bucket of boiling water in order to make the removing of the feathers easier. The legs, heart and the gizzards were used to make chicken soup, there would be no waste.

Although I was young at the time, I have fond memories of Granny Bauer. She loved to do crocheting and I even tried to join her once but I was unable to do it. My father, Toby Skolmen, used to drink Old Bucks Gin and she would use the red rings around the bottle and put them down on the doily she was creating to mark certain areas. Every morning she would wake up, sit in her special chair, and watch the driveway for one of her children to come and visit her.

When visiting Granny Bauer’s grave on 16 June 2014 with my son, I noticed there was a “wag n bietjie” plant by her grave. The name of the plant is due to the tiny thorns on the branches that hold onto you when you brush past them. Granny Bauer hated these plants, so I found it rather funny that there would be one growing right next to her gravestone.

To relieve pain from her arthritis, she would take a bee and make it sting her hand. She would also use geranium leaves and put them upside down on her body in order to draw out poison or a boil. When she had a sore she would take a lemon and rub it on the sore to heal it. She had all these natural remedies to treat anything. She had a special story that she loved to tell about baboons that would stick their hands in the beehives to get honey and get stung.” (Source: Grand-son Eddie Skolmen, 2013).

”Granny Bauer came to live with my parents in the late 1960s for about 3 or 4 months (although I had already left home by then and was working so I didn’t go up to my parent’s farm often). I remember her as a very quiet old lady, she did not speak great English and she had a strong German accent. Granny Bauer tried to teach me to crochet but I couldn’t get it right.” (Source: Grand-daughter Phyllis Bennett nee Bauer, 1990s). It seems she was always trying to pass on her crocheting skills to her grandchildren, but none of them could grasp the technique.

The Bauer homestead was located on Lorainne farm in Bluewater district. ”Life at Lorainne seems to have been simple, difficult and happy. Many stories of being stung by bees while raiding their hives for honey (a real luxury, highly prized) have been told. One of these: Hermann, with his big bushy beard, was badly stung about the head, and sat down and asked Friedrich to pull out the bee stings. Ernest (“Ansie”) and Lolly Oberem were chased by bees one very hot day. Ansie ran to the Kwelera River and dived under the water to escape the angry bees. Each time he came up for air, he saw his hat, covered with bees, floating nearby and a huge cloud of bees above him. Eventually Ansie and Lolly made their way back to the hive; now empty of bees, which were apparently still looking for the two would-be honey robbers. Needless to say, Ansie and Lolly left the unguarded honey and ran home to return another day when they had recovered and felt brave again.

Friedrich, Luise, and some or all of their children lived in a mud hut on Lorainne when their daughter Eva was born. The hut leaked and it rained when she was born, so Friedrich propped up a sail with a shotgun to protect his newborn daughter. The shotgun fell over onto Eva and her mother Luise was very upset and naturally, cried quite a lot. The scene can only be imagined and although it probably caused some harsh words at the time and concern for the newborn baby, 70-odd years later, the funny side of the story is obvious, as are the bee-stinging stories.

When Ansie was a young boy, he picked and ate mushrooms, which caused him to be violently ill as they were of the poisonous type. Distances were not easily covered, and visiting a doctor was a luxury. So his mother, Luise, treated him herself by making him drink milk, lots and lots of it. He survived with no ill effects. In fact, all the Bauer children have lived to well past middle age and more, possibly without ever having seen a doctor in their youth.

Friedrich Bauer and his immediate family moved to Illings farm in the Ladysmith district of Natal in about 1920 on the advice of a Mr Ernest Maaske, the husband of his sister, Gertrud. Mr Maaske told Friedrich that Natal was a land of opportunity and that there was plenty of money to be made. Friedrich left with his family and “10 Springbok bags (small cloth bags with a drawstring, commonly used for tobacco; measure about 15x6x9cm).” (Source: Grand-daughter Phyllis Bennett nee Bauer, 1990s).

”When the Bauer family moved to Ladysmith from East London, my father, Fred Bauer, attended school in Ladysmith and since they were very poor, he used to walk to school barefoot and put his shoes on when he got to school, then he would walk back home barefoot again. One day while walking home he was bitten by a snake and his father gave him a hiding because he didn’t have his shoes on. The snake bite was poisonous and his mother, Luise (granny Bauer), filled a drum full of fresh milk and Fred had to sit there for 12 hours with his leg in the drum to draw the poison out.” (Source: Joy Long (Nee Bauer), 2017).

”Children born to Friedrich and Luise while in Natal were Ernest, David and Norman. Friedrich’s younger brother, Heinrich, who was to stay on and run the Lorainne farm, had died of rheumatic fever at the age of 40 on 11 Feb 1932. His mother, Maria Luise, had written to him, asking him to come home to run the farm. His mother was then about 73 years old, and his father (Hermann) had died on 28 February 1914. The family returned to East London by train. They were broke.

Maria later passed away on 16 July 1937. In 1939 the Second World War broke out, and as Fritz could not accept his sons fighting “against their own people”, he got his sons back home so that they could help on the farm. Fritz actually rented another farm in the area, Rocky Villa, to ensure that they were all legitimately working as farmers. Fritz lived on the farm until his death in 1947. Luise stayed there until the 1960s when she went to live with her daughters at their various homes.” (Source: Grand-daughter Phyllis Bennett nee Bauer, 1990s).

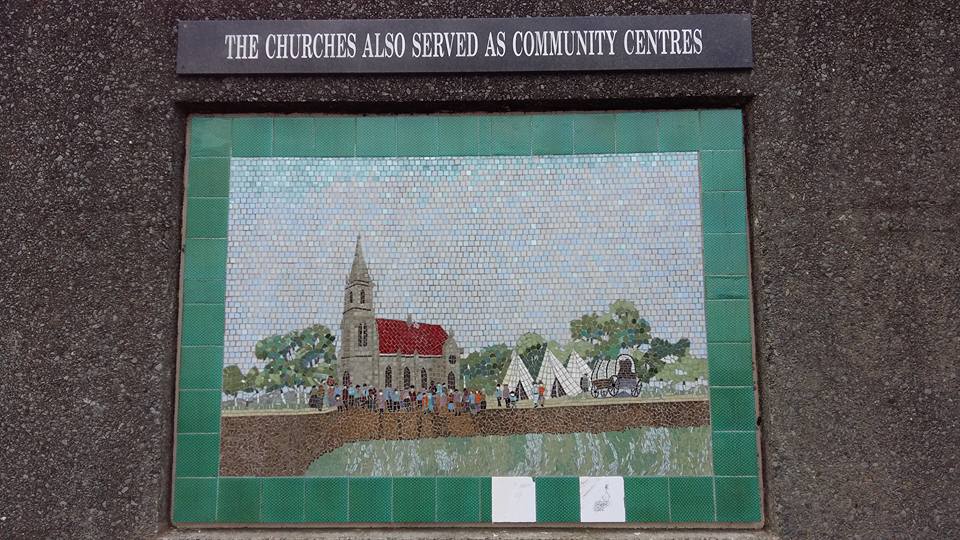

Although it is said that the families were German Lutheran, it seems there was a strong connection to the Moria Baptist Church (photograph below taken from my paternal grandmother’s old wooden box), which was the closest church to the farm in Blue Water, Kwelegha. Apparently, they “shared” the grounds at the Baptist church, but did not mix – there are even separate burial areas.

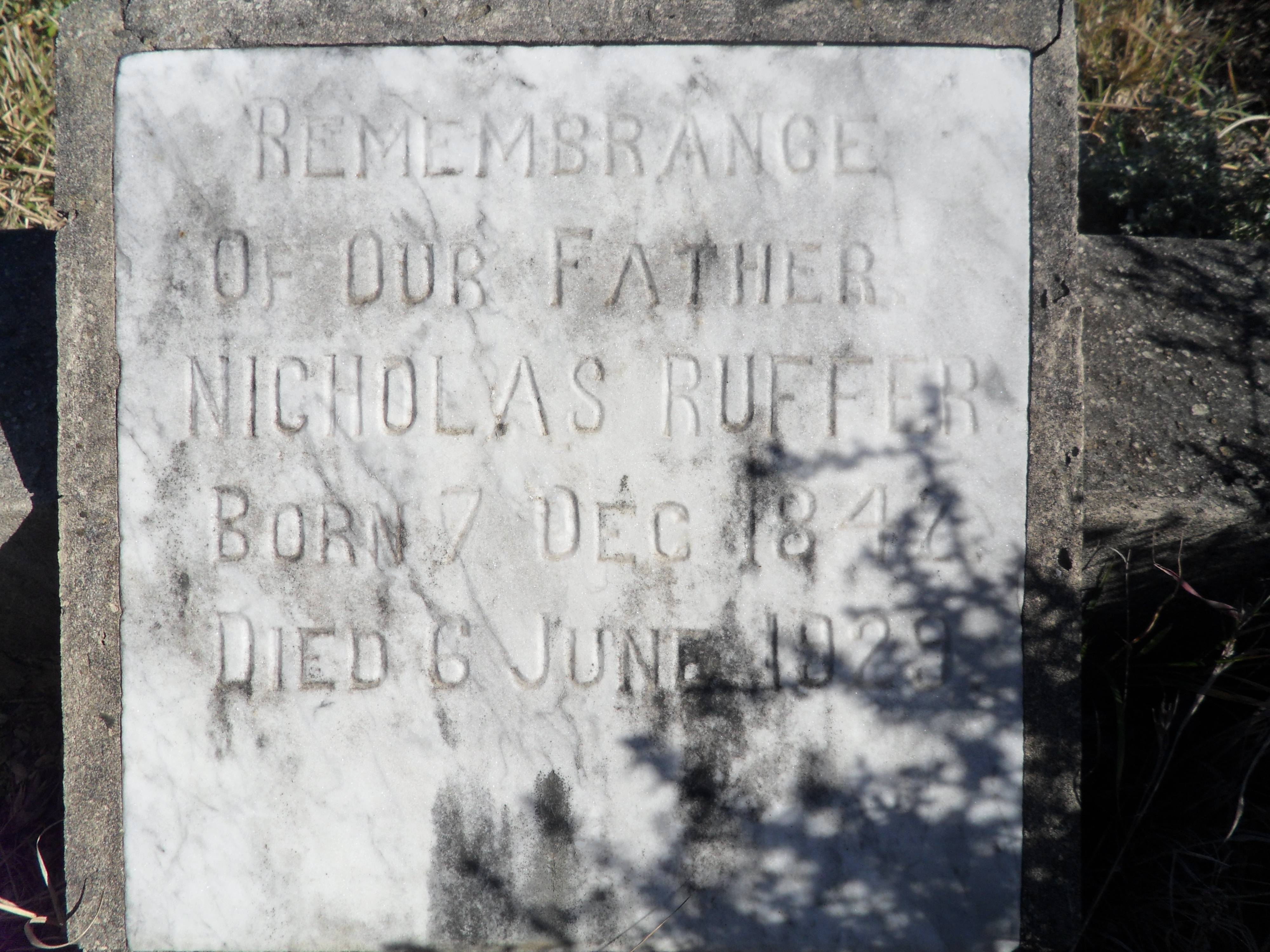

The graves of Nicolaus and Eva Rüffer, Hermann and Maria Bauer, as well as Friedrich and Luise are all located in the small upper cemetery at Moria Baptist Church in the Eastern Cape, East London district, Kwelegha, Bluewaters.

The story of the Bauer and Rüffer family is an interesting one, both families came from the same area in Germany, both emigrated to South Africa at the same time, aboard the same ship, and both settled in the same area in East London. Once they were established there, both families had children, and two of these children got married which joined these two German families even further. Though they went through hardships, they built a good life in South Africa and prospered in their new home.

Remembering the German Settlers

The influence of the 19th-century German settlers can still be culturally felt and seen in the names of suburbs and buildings around East London and, elsewhere in the Eastern Cape, in the names of towns such as Berlin, Potsdam and Stutterheim.

In 1957, a German Settlers Memorial monument was commissioned to celebrate the centenary of the arrival of the first of the German Settlers in 1857. The funding was provided by the German government and the cities of Potsdam, Braunschweig, Berlin, Hanover, Frankfurt and Breidbach.

On 4 September 1961 the German Settlers Memorial statue was completed and unveiled in East London by Mr O.E Heipertz, the Consul of what was then West Germany. The three-figure granite statue was sculpted by Lippy Lipshitz and stands on the slopes of Signal Hill on the Esplanade of East London.

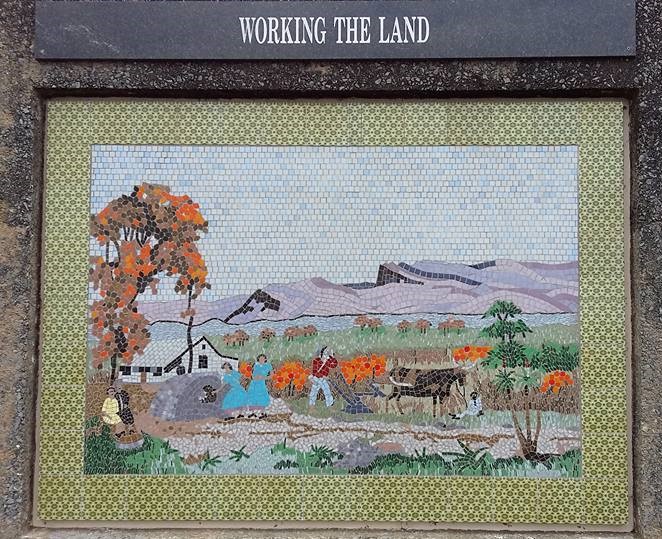

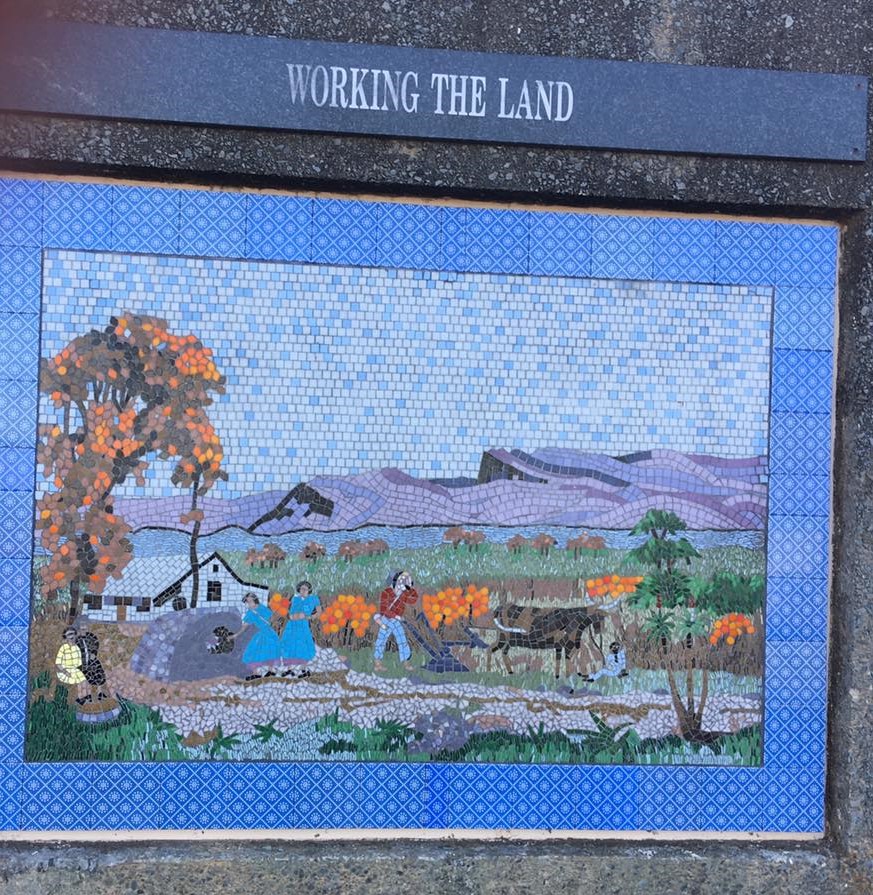

Behind the sculpture is a wall, originally displaying five large bronze plaques designed and made by German sculptor, Bodo Kampmann. The plaques depicted the farewell from Germany; the voyage to South Africa; building a home; ploughing the land; and the family looking into the future. However, the bronze plaques were stolen in the late 1990s, and as they could not be replicated, were later replaced by five 1.4m x 2m plaques of a new design and medium (mosaic) that were grouted onto the walls on 11 January 2015. The mosaics were cut, arranged and mounted by a Cape Town art company, Mosaic Works. (Source: Heroes Park art installed in a stink, Mike Loewe, Daily Dispatch, 2015).

The original bronze plaques:

The replacement mosaic plaques:

The new German Settler monument murals were officially opened on 22 May 2015.

“Often overlooked by residents, this site attracts many foreign tourists, who come to admire the father, mother and child granite figures that form the focal point of the memorial, facing out to the ocean and the future.

This regional memorial to the arrival of more than 2000 German men, women and children settlers has, over the years, cemented itself as one of the icons of East London’s Esplanade.” (Source: Nightjar Travel).

A German Settler Gallery has also been created in the East London Museum. This has information on the history of the settlers, a diorama of a country cottage, with wagons and agricultural equipment on display. The interior of a home belonging to Mr F. Alberti, a wealthy wool buyer from East London, is also on display reflecting a comparison of rich and poor homes.

About the Author

For more articles visit Dayne’s Discoveries Blog, browse our online shop, or contact us to share information, stories, or photographs relating to the 1878 East London German Settlers.

Hi Dayne,

I stumbled across your blog post in search of information on my mother’s biological parents. Her family name is said to be McLaughlin but I don’t know how to go about searching for any records since she never knew her biological parents. See, my mom was abandoned as a baby during the terrible floods in August 1970.

I would appreciate your guidance on how to go about connecting the dots.

Please email me at chanteanamay@gmail.com

Thank you.

LikeLike

Good day I’m researching the Scottish Immigrants particularly the James Mackenzie family that arrived in South Africa around 1877. During your research did you ever come across this name researching the Immigrants of the East London, Gonubie and Komga area. They settled on Lot 22 Gonubie area. James was particularly instrumental in establishing the Gonubie Presbyterian Church around 1902. He was a stone mason at trade and built many buildings and bridges around the East London area between 1877-1907. He was then followed in the trade by his 6 sons that came with him to East London. In particular his son Robert Hay Mackenzie.

Any information or guidance as to where I could start searching for information and documentation will be greatly appreciated.

Kind Regards

Annette Connellan

You can contact me on 0827878289 or email nconn@mweb.co.za

LikeLike

Fascinating and informative. Thankyou. I too am researching family history and will look through the references. I located the name of my great, great grandfather, Carl Beckerling, in the list of passengers aboard the Sophie that sailed from Hamburg to East London on 15 August 1877. I found this list at http://www.geocities.com/heartland/meadows/7589/Names/schiff_23.html

Doubtless there is a more direct route but this is one I stumbled on. The ancestral Beckerling arrived from Elmshorn without his newly married wife and young child. I guess they followed later.

I look forward to reading through all of your excellent references.

Louis Beckerling

Perth, Western Australia

LikeLiked by 1 person

My mothers’ surname was von Beyer. When the von Beyers have arrived in South Africa I have no idea so I cannot discover more about my ancestors.

LikeLike

Hi Liesel.Im trying to find more information on my Grand farther Nick Ruffer who settled in South Africa married a colored lady Latitia her maiden surname was Snyman , what i would like to know if you able to tell me more about my grandfather side …….if he had more family with him when he immigrated.

LikeLike

Hi Greg,

I have never researched the Rüffer family line. Unfortunately I cannot answer your question.

For you, I searched for your Grandmother and found her Estate using NAAIRS:

DEPOT KAB

SOURCE MOOC

TYPE LEER

VOLUME_NO 6/9/21523

SYSTEM 01

REFERENCE 5068/

DESCRIPTION : RUFFER, LETTIE ANNIE. BORN SNYMAN. ESTATE PAPERS.

STARTING 1953 ENDING 1953

And can be viewed at: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-99V2-C4DT?i=74&cat=2212749

It is sad to see that Lettie died on 11-11-1952 at the young age of only 24yrs 9 mths. Her children are listed as Kathleen Ritha, Ronnie Royden & Rowan John August. Per a letter (attached to this estate) dated 11-11-1953 Nicolaas stated his intentions to remarry.

From her death notice we now have your grandfather’s full name of “Nicolaas August Rüffer”.

My suggestion to you is that your register online (FREE) to FamilySearch.org

Once you have signed up then follow this link to where I have added your grandfather’s name to the search engine: https://www.familysearch.org/search/record/results?count=100&m.defaultFacets=on&m.facetNestCollectionInCategory=on&m.queryRequireDefault=on&q.birthLikeDate.from=1800&q.birthLikeDate.to=2021&q.givenName=Nicolaas%20August&q.recordCountry=South%20Africa&q.surname=R%C3%BCffer

There is an online family tree where you will see that Nicolaus (ID: G752-19J) is the son of August Friedrich Heinrich Rüffer & Elizabeth Auguste Sangerhaus.

This is the link to the family tree directly to Nicolaus and you may then navigate as you wish and add any missing information: https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/details/G752-19J

Happy Hunting!!

Regard, Liesel

LikeLike

Thanks Very much for this information Liesel ….I will follow up and make use of all the information sent to me.

LikeLike

Hi Greg,

update from my previous mail…

I did actually find the connection and you will too when you view the family tree online (which I discovered after finiding the initial information)

Basically, your grandfather Nicolaus Ruffer older son of August Friedrich Heinrich and August is the youngest and and only son of Nicolaus Ruffer the settler into SA

LikeLiked by 1 person

My mother’s surname was Beyer. I believe it was von Beyer but during the war they changed it to Beyer as they did not want to be known as Germans. Do anybody know when the Beyers arrived in South Africa?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Morning Dayne. I have been following your articles with great interest. Your Grandfather Tobie and grandmother Eva had the farm directly opposite mine “Green Gates” The day that the German Settlers Memorial was unveiled was an extremely hot day . During the ceremony the soldiers stood at attention . I think this was the reason why 3 of them toppled over with heat exhaustion.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article, thank you. Were the Hagemann families part of 1878 settlement. If I’m not mistaken there were quite a few families on the farms in the area of the church in the 1980’s?

LikeLike

Very interesting Thanx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Im looking for info on william bauer who had 4 children born between 1900 and 1918

LikeLike

Hi. Im not of Bauer stock, but Durrheim, on my mother’s side, of the civilian 1858 settlers. A new discovery on my part, as I was adopted at birth. From Grimmen and Berhholz in the old Prussian Federation. I have a 200 page document, compiled by Erleen West on the family.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I too am a Durrheim descendant. I wish I could lay my hands on a copy of the West book.

LikeLike

Very interesting article. Please note that the brass plates of the German memorial were ripped off by criminals in 1999.They were replaced by mosaic art works depicting the German history in 2014.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks, Celia. I have updated my article with this information.

LikeLike

Hi Dayne,

Thanks for an interesting read!

I have Heinrich Hermann Rudolf Paul Bauer marrying into my paternal line, to Helene Emilie Elizabeth Puchert (Lena).

Family research is a wonderful addiction!!

Liesel

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Liesel,

Do you have any information, pictures or stories about Heinrich? From my family tree I can see that they had 4 children: Theodor Bauer (born 10 Feb 1914), Emil Bauer (born 2 Jul 1917), Hilde Louise Bauer (born 2 Oct 1921), and Edwin Heinrich Bauer (born 2 Jan 1925). The only further information I have on this branch of the Bauer tree is that Edwin married Vera Louise Rosie.

LikeLike

Hi Dayne,

I have the same info from Heinrich’s Death Notice. In addition to that Theodor’s married Irene Hildegard (maiden name unknown).

Also I went on a little ‘hunt’ this evening and I have just located the estate file for Hilda’s husband, Christian Otto Andreka!!

You will find some new information on Estate file No 1800/1981: https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSLQ-2952-G?i=1&cat=2772480

Christian was previously married to Martha Louisa DURRHEIM b. 24-4-1906 d, 21-8-1934 Ref: 44593 – they had no children at the time of her death per her DN (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C91W-LYHY?i=504&cc=2517051&cat=331262 ) which confirms that Hilda is the mother of the children listed on his DN.

Martha’s gravestone is found at:

http://www.graves-at-eggsa.org/main.php?g2_itemId=670355)

I have no further information on this Bauer line.

Helene’s father & my great grandfather were brothers.

Unfortunately I have no photos either.

Let’s hope I find more information in the future…

LikeLike

Thank you, Liesel. Much appreciated. I will add this information to my tree 🙂

LikeLike